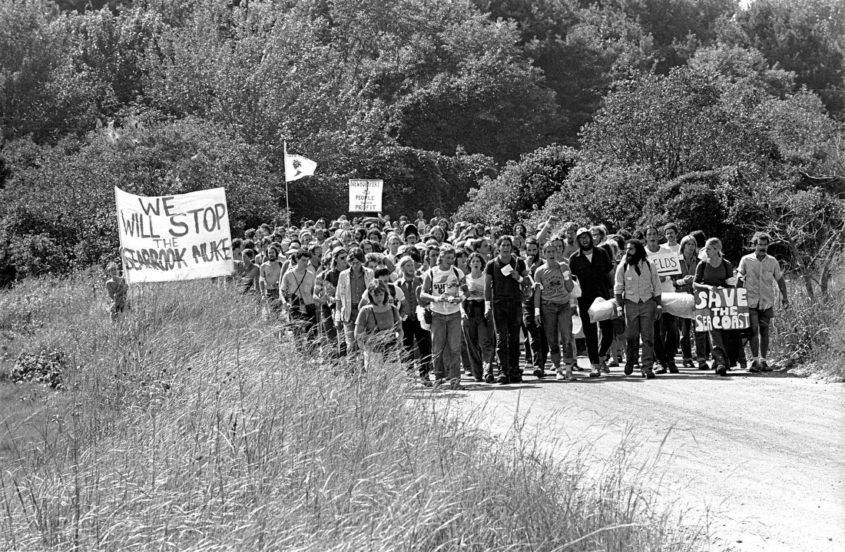

When the federal government issued a construction permit for a nuclear power plant in Seabrook, New Hampshire in 1976, despite the opposition of local towns and growing alarm about nuclear technology, activists from New Hampshire and neighboring states decided it was time for direct action. After forming a group called the Clamshell Alliance and getting trained in the techniques and principles of active nonviolence, 18 of the group’s members, all New Hampshire residents, walked down the Seabrook railroad tracks to the plant’s construction site, where they were arrested for criminal trespass on August 1. Three weeks later, a group 10 times larger returned for another demonstration and another round of mass arrests. The following spring, 2000 people took over the construction site for a weekend, with 1415 “Clams” arrested and hauled to National Guard armories. Hundreds of them, practicing “bail solidarity,” remained in the armories for almost two weeks.

[Read the Clamshell Alliance Founding Statement here.]

Issues that drew activists into the movement included the dangers posed by low-level emissions of radiation from nuclear fuel production and normal reactor operations, the risk of a major accident, the high cost of construction, the absence of a safe disposal method for reactor waste, the dangers of nuclear proliferation, and the availability of renewable alternatives. The proximity of beaches crowded with thousands of summer vacationers made the safety issues especially compelling. At every turn, arguments by grassroots activist groups were countered by slick PR from the nuclear utilities and their allies.

[Read the Clamshell’s “Declaration of Nuclear Resistance” here.]

The Seabrook mass arrests weren’t exactly the beginning of nonviolent protest against “nukes.” In 1974, Sam Lovejoy, a member of a radical commune in Montague, Massachusetts, had been arrested for toppling a weather tower at the construction site for a nuclear plant next to the Connecticut River. Ron Rieck, a member of the Greenleaf Harvesters, was arrested sitting atop a weather tower at Seabrook in January 1976. And in Wyhl, West Germany in 1975, thousands of farmers had successfully occupied a nuclear construction site until a nuclear plant was cancelled. Once the Clamshell Alliance began mass occupations, the “No Nukes” movement spread rapidly through the USA spawning similar “alliances” that took action against proposed and operating nukes from Maine to California, Seattle to South Carolina.

As Joanne Sheehan of the War Resisters League has written, the keys to the No Nukes take-off included a commitment to nonviolence and training; the use of small “affinity groups” for mutual support, planning, and decision-making; and a non-hierarchical structure consistent with emerging feminist ideology. Together, those elements invited participation and unleashed creativity that captured public imagination while driving the pro-nuke forces nuts.

The Alliance was made up of small groups spread throughout New England, from southwestern Connecticut to eastern Maine. Most were local committees, which in addition to joining protests at Seabrook also conducted community education projects and campaigned to shut down other operating and planned reactors. Other Clamshell groups were ephemeral affinity groups which organized themselves for actions and then dissolved. Representatives of local and regional Clamshell groupings met for regular “Coordinating Committee” meetings to conduct the Alliance’s business, mostly planning for the next demonstration, with decisions made by consensus. Committees dealt with nitty-gritty issues of nonviolence training, resource production, fundraising, labor outreach, and legal support for Clams who had been arrested. A staff collective based in Portsmouth coordinated planning, communication, fundraising, and publication of the Clamshell Alliance News.

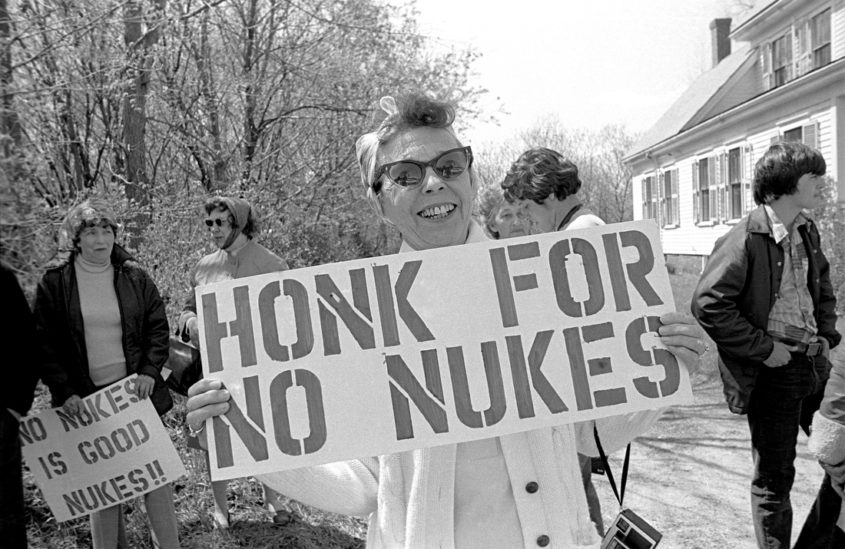

As the Clamshell grew, fractures within its membership became more apparent. In 1978, plans for an even larger fourth site occupation were thrown into confusion when Tom Rath, New Hampshire’s attorney general, proposed allowing a lawful demonstration at the construction site as long as everyone agreed to leave afterward. With local media labelling Clams “terrorists” and some area residents receiving threats of retaliation if they allowed occupiers to camp on their land, the offer had significant local appeal. When the Clamshell agreed to accept the offer, dissidents who were wedded to direct action rebelled, initially forming a “Clams for Democracy” caucus that argued acceptance of the “Rath Proposal” had violated the group’s norms. The 1978 rally attracted almost 20,000 people, including many local residents who would not have gotten near an act of civil disobedience. But the rift in the Clamshell would not heal.

[For more about the Rath Proposal and its impact, read this reflection by Cindy Girvani Leerer.]

Following the Three Mile Island meltdown in 1979, Clams associated with the dissident caucus called for another site occupation, one which would require penetration of the fences surrounding the construction site, which by then held lots of valuable heavy equipment and two partially constructed nuclear reactors. In addition, the ultra-right-wing governor, Meldrim Thomson, whose handling of the earlier demonstrations contributed to their success, had been replaced by Hugh Gallen, a centrist Democrat elected largely based on his opposition to the rate hikes Public Service Company had demanded to pay for the nukes. When a Clamshell Congress failed to approve an occupation that would involve fence-cutting, the proposal’s proponents, many based in the Boston area, created a new group, the Coalition for Direct Action at Seabrook (CDAS).

While the Clamshell organized a nonviolent campaign to block delivery of the reactor pressure vessel and protested investments in nuclear power by blockading the New York Stock Exchange on the fiftieth anniversary of the “Great Crash,” the splinter group organized site occupations with more emphasis on direct action than nonviolence. CDAS demonstrations in 1979 and 1980 were more physically aggressive (including use of wooden shields, bolt-cutters, and grappling hooks to take down fences) than the prior Clamshell actions and were met with physical resistance rather than mass arrests. This time, the state’s behavior was perceived in a more favorable light than that of the demonstrators.

For most of the next decade, construction proceeded without mass protest. Demonstrations picked up again during the battle over an operating license, held up over doubts that the area could be safely evacuated in the event of an accident. Civil disobedience actions, in which hundreds of people climbed hinged ladders over the fences, resumed, but their ritualistic nature lacked the creative defiance of the earlier demonstrations. When George H. W. Bush, backed by pro-nuke Governor John H. Sununu, defeated anti-nuke Mike Dukakis for president in 1988, an operating permit soon followed. The Clamshell Alliance gradually dissolved.

While public memory of the Clamshell Alliance mostly centers on mass arrests and jailings, it’s important to note that the Clams always made use of a range of tactics, including running for public office, cultural expression, opposing rate increases needed to finance nuclear construction, advocacy for getting publicly-owned utilities out of the nuclear business, and even trying to win allies among stockholders of privately-owned utilities whose investments would be placed at risk in nuclear accidents. By the time the Three Mile Island reactor in Pennsylvania melted down in 1979, No Nukes awareness was broad enough that signals from Wall Street and Capitol Hill sent the nuclear industry into a coma from which it has not recovered. One of the two planned Seabrook reactors was cancelled and the nuke’s main sponsor, Public Service Company of NH, went bankrupt and was absorbed by Northeast Utilities (now Eversource). Most of the other planned nukes were cancelled. Seabrook, which went into operation in 1990, was just about the last reactor to go online. [It is currently owned by Florida-based NextEra Energy Resources.] We can only wonder where we’d be today if the calls for rapid expansion of solar, wind, and hydro as alternatives to nuclear had been heeded in the 1980s.

The Clamshell Alliance should also be remembered for its links to social justice movements in countries such as the Philippines and South Africa, where dictatorships were promoting nukes, and for its ties to Native American groups resisting exploitation of natural resources in their traditional lands. The Alliance’s promotion of active nonviolence, mass civil disobedience, training, affinity groups, and consensual decision-making were influential in the movements of the 1980s, including anti-apartheid, LGBT rights, and environmental campaigns. The revival of the nuclear disarmament movement in the late 1970s can also be attributed in part to the popularity of the No Nukes cause. The 1999 shut-down of the World Trade Organization in Seattle and the Occupy Wall Street movement can be seen, as well, as Clamshell descendants.

In New Hampshire, many members of the Clamshell went on to active involvement in electoral politics, alternative energy, the labor movement, nonviolent training, and alternative energy businesses.

[Claimer: Arnie was active in the Clamshell and served the Nonviolence Training Committee and from 1978 to 1979 as a member of the office staff collective.]

Read about the formation of the Clamshell Alliance in an oral history produced by Al Giordano.

Read first-hand accounts from the Clamshell Legacy and Antinuclear Mobilization project.

Paul Gunter, who was one of the first 18 occupiers and later served as a staff person, moved to Washington DC where with his wife Linda he started a new organization, Beyond Nuclear, which continues to support organizing, advocacy, and education about the dangers of nuclear power and weapons.

Films about the Clamshell Alliance include “The Last Resort,” produced by Green Mountain Post Films, and “Seabrook 77,” by Robbie Leppzer of Turning Tide Films.

More photos of Clamshell actions and those of other No Nukes groups can be found in a collection, To the Village Square, by Lionel Delevingne.