When Mary Tompkins and Alice Ambrose arrived in Dover, New Hampshire, in 1662, you might say the Quaker missionaries were asking for trouble. They soon found it.

Dover, which consisted of a settlement near what we now call Dover Point, was under the rule of strict Puritans, allied with the leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in Boston. There, Quakers had already faced persecution and death.

From 1656 to 1661, according to the Global Nonviolent Action Database, “at least forty Quakers came to New England to protest Puritan religious domination and persecution. During those five years, the Puritan persecution of Quakers continued, with beatings, fines, whippings, imprisonment, and mutilation. Many were expelled from the colony, only to return again to bear witness to what they believed … The Boston jails were full of Quakers, and four known executions of Quakers took place in Massachusetts during those five years.”

Among the victims were William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephenson, who were hung in 1659 after remaining in Boston following banishment by the local authorities. Mary Dyer, who was to have been executed along with Robinson and Stephenson, was removed from the gallows only to face her own execution the next year.

Despite the known risk, Tompkins and Ambrose attempted to convene Quaker worship sessions in Dover. Their beliefs, especially that everyone has access to God’s truth without need for clergy or scripture, were not tolerated by the local Puritan elite. The women were ordered to leave town with a warning they would face severe punishment if they were to return.

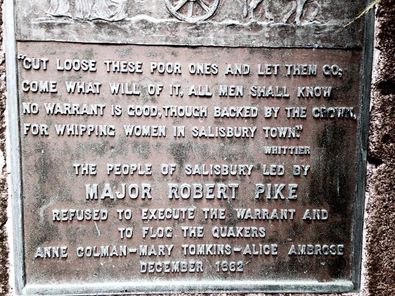

After a sojourn across the Piscataqua, Tompkins and Ambrose did return later that year, joined by Ann Coleman. They were speedily arrested with punishment ordered. “You and every of you are required, in the king’s name, to take these vagabond Quakers, Ann Coleman, Mary Tomkins, and Alice Ambrose, and make them fast to the cart’s tail, and driving the cart through your several towns, to whip them on their backs, not exceeding ten stripes each on each of them, in each town, and so convey them from constable to constable, until they come out of this jurisdiction, as you will answer it at your peril; and this shall be your warrant,” read the order of magistrate Richard Waldren (whose name has various spellings). Expelling them from the jurisdiction of the Massachusetts Bay Colony would require them to suffer beatings in Dover, Hampton, Salisbury, Newbury, Rowley, Ipswich, Wenham, Lynn, Boston, Roxbury, and Dedham.

In the dead of winter, Tompkins, Ambrose, and Coleman were lashed to a cart, stripped to the waist, and whipped. Then they were transported to Hampton, where the punishment was repeated. When they reached Salisbury, local authorities being less cruel or perhaps their sympathy aroused by the women’s spirit, the three missionaries were released.

After another sojourn in southern Maine, the missionaries returned to Dover where they were once again arrested, forcibly dragged through the snow to the river, and threatened with death by drowning. As fate, or Providence, would have it, a fierce wind rose up and forced the Puritan constables back indoors, sparing the women’s lives once more.

The three Quaker women faced other persecutions elsewhere but did not return to Dover. However, according to historians, one-third of Dover’s population was Quaker within a few years.

Their story was captured years later by Quaker poet, John Greenleaf Whittier, in “How the Women Went From Dover.”

As for Richard Waldren, he was later murdered by Abenaki warriors after he lured members of their community to his settlement at Cocheco, from which 200 of them were kidnapped by local and Boston militia.

Read more about “The Persecution of Early Quakers in America” on a website created by Hall and Joan Worthington.

Read a deeply researched by fictionalized version of the story, Vagabond Quakers, by Olga Morrill (Morrill Fiction, Madison NH, 2017).