Inside the Palmer Raids

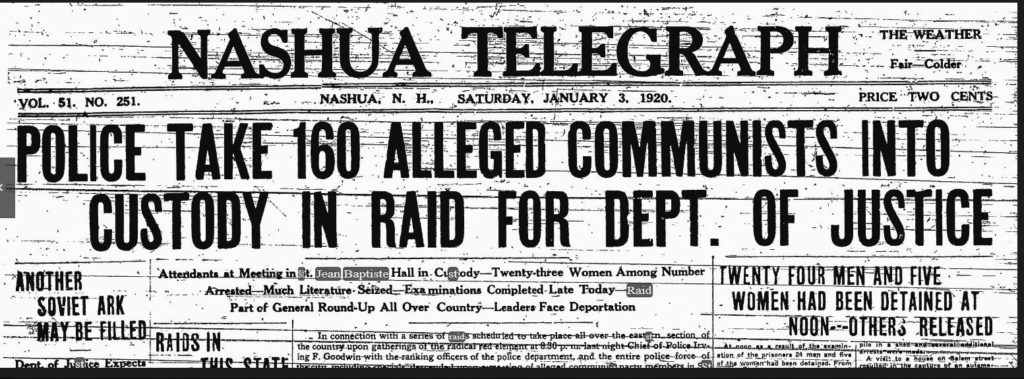

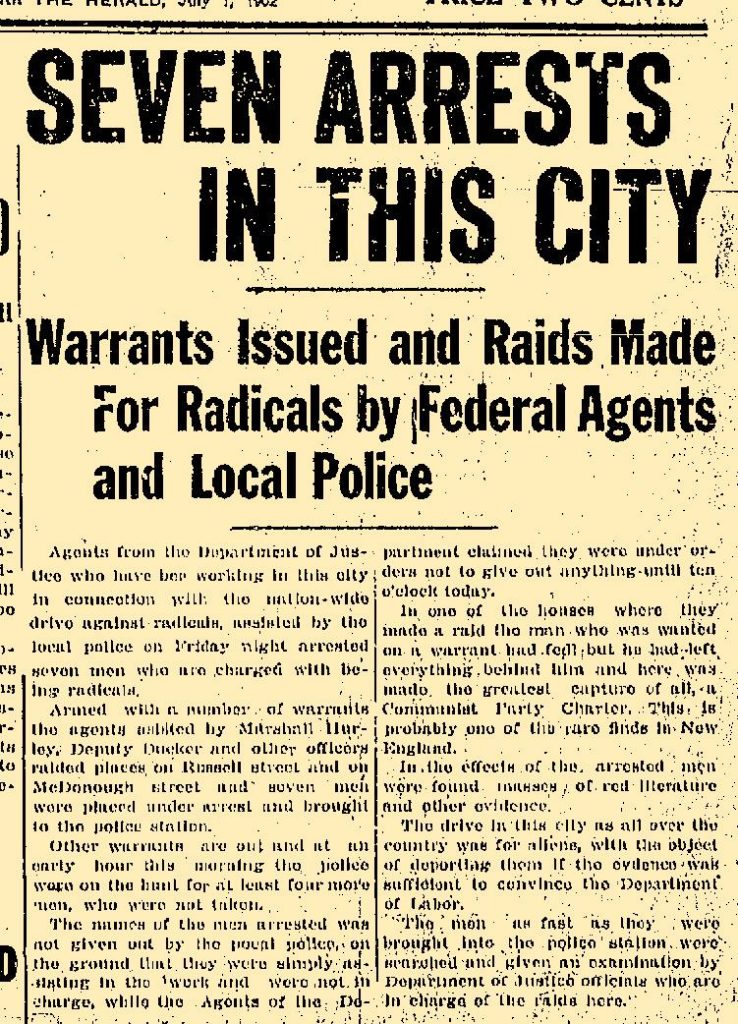

On Friday evening, January 2, 1920, federal agents and local police swept through eight New Hampshire cities and towns, searching for people they claimed were dangerous radicals. When the raids were over, nearly 300 New Hampshire residents, mostly immigrants from eastern Europe, were in custody, seized from private homes and meeting halls in Nashua, Manchester, Derry, Portsmouth, Claremont, Newmarket, Berlin, and Lincoln. If they were both “aliens” and members of the Communist Party, they would be subject to deportation.

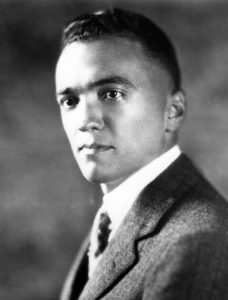

The Palmer Raids, as they became known–in dishonor of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer–netted as many as 10,000 people in 33 cities nationwide, with the 141 captured in Nashua the largest single mass arrest in the country. The raids also propelled the career of a young Department of Justice attorney, J. Edgar Hoover, whom Palmer had appointed to head the General Intelligence Division (originally named the “Radical Division”) inside the DOJ’s Bureau of Investigation (later renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or FBI). Hoover began compiling a massive file of index cards and dossiers, one for each person suspected or accused of being a radical, no matter how slight the evidence.

During World War I, crackdown on dissent had focused on German sympathizers and anti-war activists (including socialists and Wobblies). But after the war and the Russian Revolution, it shifted smoothly to anarchists and communists, especially immigrants from eastern Europe.

Although federal wartime laws which had enabled the jailing of activists such as Eugene V. Debs were no longer valid, dozens of states stepped into the void. According to historian Robert Murray, “by the year 1921, there were thirty-five states plus two territories (Alaska and Hawaii) which had in force either peacetime sedition legislation or criminal syndicalist laws, or both.”

New Hampshire was no exception. According to historian David Williams, A. V. Levensaler, who headed the Bureau’s Concord office, drafted the state’s anti-Bolshevist bill, which was adopted by the legislature and signed into law by Governor John Bartlett in March 1919. The law made it a serious crime to “advocate or encourage by any act or in any manner” the overthrow or change of government of the United States, the State of New Hampshire, or any of the state’s subdivisions. In addition to criminalizing such advocacy in public or private settings, the law banned the publication, distribution, and possession of any printed or written material, including pictures, deemed to be of seditious intent. Any such materials were to be seized and destroyed.

Another section of the law made it a crime to advocate, incite, or encourage “the violation of any of the laws of the United States, or this state, or any of the bylaws or ordinances of any town or city therein.”

The penalty for violation was up to 10 years in jail, a fine of up to $5000, or both.

Under orders from Washington to compile lists of alien radical leaders, Bureau agents used warrantless break-ins, planted listening devices, cultivated informers, and hired infiltrators to identify subversives inside unions and ethnic social clubs, especially those from eastern Europe, often labeled “Russians” regardless of where they were born.

In the words of historian Regin Schmidt, the Red Scare, orchestrated and largely led by A. Mitchell Palmer, J. Edgar Hoover, and their Department of Justice colleagues, “was, at bottom, an attack on … movements for social and political change and reform, particularly organized labor, blacks and radicals, by forces of the status quo.” But Palmer, Hoover, and the others faced a serious obstacle: they had no authority under federal law to prosecute people simply for being union members, Black, or radical. That’s one reason why they targeted immigrants. Immigration was regulated by the Labor Department, and its rules said anarchist aliens could be deported.

By December 1919, following months of preparation, the agents were ready. Following instructions from Washington, New Hampshire’s Bureau agents used the flimsiest of evidence or none whatsoever to draw up arrest warrants.

Friday evening, January 2, 1920, began like most other Friday evenings, writes Williams. “That evening people in the ‘Russian’ communities gathered together at their clubs, some to hear socialist speakers, while others danced, played cards, or shot pool. An unexpected knock at the door and the sudden appearance of government agents broke up the parties. The fact that the agents had no search warrants or warrants for the arrest of many of the people did not stop them from detaining everyone present.”

In Manchester, agents found and arrested 54 people at the Tolstoi Club, a hangout for Russian workers on Central Street. In Nashua, agents arrested 141 people at the St. Jean Baptiste Hall on Chestnut Street, which had been rented for the evening by the Lithuanian Club. In Portsmouth, they sought members of Open Forum, a leftwing caucus within the local labor movement. And In Claremont, agents arrested 23 people, mostly at Joe’s Russian Baths on Main Street. “The prisoners were astonishingly ignorant of anything pertaining to Sovietism, and it required considerable ingenuity and threatening persuasion to get anything out of them,” a Claremont paper reported.

In addition to ethnic social clubs, agents targeted private homes and businesses. John Bellows, a member of Open Forum, was arrested while playing cards with his brother Stanley in the back room of Stanley’s Portsmouth grocery store on Russell Street. Stanley was arrested, too, for good measure. Koly Honchekoff, another Open Forum member, was at home in bed when he was captured. Asked at a hearing if he was a union member, he answered in the affirmative, adding he had been one for three years. As Williams recounts, “the interrogator put down three years in the Communist Party and the questionnaire became part of the official record.”

Two days later, Manchester police “took 140 men and women from Manchester to Boston aboard the train labeled ‘the Red Special,’” writes David Williams. “Arriving in Boston, the prisoners marched handcuffed and in chains through the streets to the ferry landing. Officials made a special effort to attract attention to the spectacle, inviting newsmen and photographers to record the event.” There, the New Hampshire detainees joined some 400 others at Deer Island, where they were held incommunicado in frigid and unsanitary conditions.

The exact number who were arrested, convicted, and/or deported is unknown. Probably, most of the New Hampshire contingent was released based on the lack of evidence and reaction to the way they were treated. It was the climax of the Red Scare.

But the Red Scare never went away, and in the words of Regin Schmidt, “institutional and bureaucratic anti-radicalism, once introduced and established in 1919, became a permanent feature.”

Although a peacetime sedition law never came to be, Congress in 1920 made it a deportable offense to even possess radical literature. And in 1921 and 1924 they tweaked the immigration laws yet again to set quotas aimed at reducing immigration from countries in eastern and southern Europe where most of the radicals came from. Congress also barred Asian immigration entirely and established the U.S. Border Patrol.

As for J. Edgar Hoover, he became Acting Director of the Bureau of Investigation in 1924. From that perch, he continued spying on and attempting to destabilize radical groups all the way through the 1960s.

New Hampshire’s sedition law stayed on the books until 1973. In the second Red Scare, New Hampshire adopted a law banning “subversive activities” in 1951 and two years later appropriated funds to enable Louis Wyman, the attorney general, to investigate cases of subversion. Wyman looked high and low, sent two men to jail for refusal to cooperate with his inquisition, and published a lengthy report detailing his findings. But he never charged anyone with the crime of being a “subversive.” A 1949 act stating that “No teacher shall advocate communism as a political doctrine or any other doctrine or theory which includes the overthrow by force of the government of the United States or of this state in any public or state approved school or in any state institution” is still in force at the time of this writing.

You can read a longer, more detailed version of this story at InZaneTimes.

For more about New Hampshire’s second Red Scare, read about Willard Uphaus and Hugo DeGregory.

Sources for this story included:

David J. William, “’Sowing the Wind’: The Deportation Raids of 1920 in New Hampshire,” Historical New Hampshire, Spring 1979. This article was based on Williams’ dissertation, “’Without Understanding”: The FBI and Political Surveillance, 1908-1941,” completed in 1981.

Regin Schmidt, Red scare: FBI and the origins of anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943, Museum Tusculanum Press 2000. Downloaded in 2021 from Open Access, ,https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/34930.

Robert K. Murray, Red Scare – Study Of National Hysteria, 1919-1920, McGraw Hill, 1964.

Also worth reading:

Ann Hagedorn, 1919: Hope and Fear in America, Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2007.