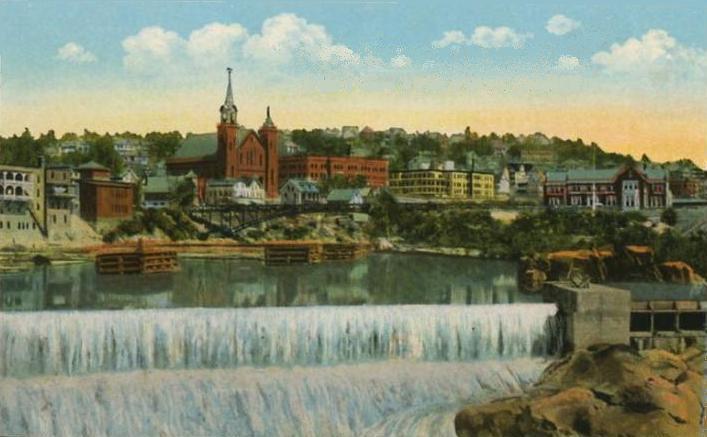

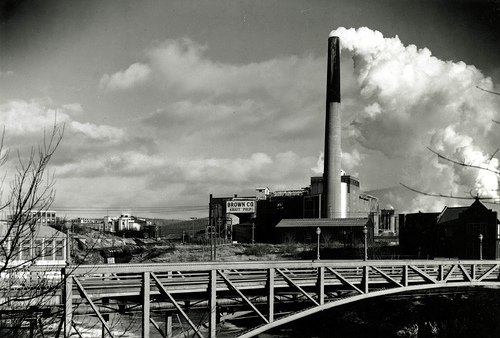

When Arthur Bergeron returned to his hometown of Berlin, New Hampshire, after attending Dartmouth College and Harvard Law School, the city’s workers were agitating for change. The year was 1934, and the Great Depression had forced cutbacks in the paper industry that left the city reeling. The Brown Company, the city’s dominant economic power, had cut wages by 10% in March 1931 and laid off all unmarried men. That fall they cut wages another 10%, did so again the following spring, and abolished extra pay for overtime.

Not only that, but with political leadership tied to paper company interests, there was little restraint on corruption. The city’s treasurer, John Labrie, had a habit of depositing city funds in his personal bank account, probably pocketing the interest until he turned it over to the City. When the bank was shuttered in 1932, the funds were frozen. Berlin was out $72,000.

William Corbin, who served as mayor while working for Brown and running a bank, was willing to sue to get the money back. But when his term ended, the new mayor, Ovide J. Coulombe, pulled out of the lawsuit. Instead, he blamed Berlin’s ills on welfare payments to “men who are loafing.”

Members of the community, many of them millworkers, responded by forming the Berlin Taxpayers Association with plans to file a new lawsuit. But none of the city’s well-established lawyers, all tied to the dominant economic interests, would take the case.

Enter Arthur Bergeron, fresh out of law school. He agreed to represent the Taxpayers and in 1934 won a judgment against Labrie and a bonding company. Bergeron did not stop there. With his help, members of the Taxpayers Association formed the Coos Workers Club, which soon had thousands of members. According to Eric Leif Davin and Staughton Lynd, “Its first success was the restitution by the Brown Company of extra pay for overtime work. Then the club procured a higher minimum wage for mill workers and a twenty-five cents per cord raise for Brown Company loggers in the woods.”

Bergeron was named editor of the club’s newspaper, the Coos Guardian, which he called the “official mouthpiece of the Coos County Workers Club, the veterans, the farmers, the taxpayers and all other individuals or groups who have a just cause.”

Holding that “the class of people who had the least to do with bringing about the depression nevertheless has to suffer the most, simply because they are not in control of the government,” the Workers Club launched itself into politics by forming the Berlin Labor Party and running candidates for mayor and city council in 1934. Its platform included calls for transparency in government, such as requiring that meetings be held in public and that salaries for all public officials be disclosed. Phillip Glasson, a Brown employee who served as the Party’s secretary, later said, “One of the main reasons for the party was to get control of the political setup so that they couldn’t bring in the National Guard in case of a strike.”

David Feindel, the Labor Party nominee for mayor and president of the electricians union, was elected. Three more party members were elected to the City Council. But with the major parties holding onto a majority of Council seats, Feindel was unable to move much of the Party’s platform.

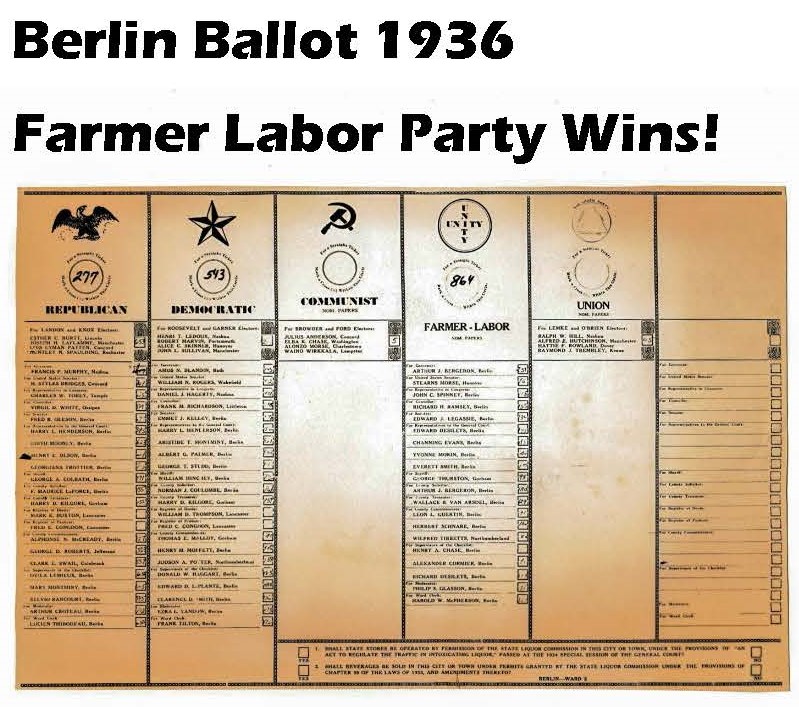

While local organizing continued in Berlin, efforts to expand connections in more rural parts of Coos County and an affinity with similar political developments in the Midwest led to a name change. Meeting on July 10, 1934, the Workers Club changed the party’s name to “Farmer Labor Party.” According to Linda Upham-Bornstein, “By and large, the Coos County Farmer-Labor Party was not comprised of strident ideologues. Nevertheless, the party platform was certainly radical for its time, at least to the extent that it proclaimed that fundamental social change was imperative.”

In the 1935 election, with the bilingual Arthur Bergeron topping the ticket, the party’s outcome improved. “The predominantly French-Canadian city voted overwhelmingly in favor of the entire Farmer-Labor Party slate of candidates, giving the party control of the city government,” writes Linda Upham-Bornstein. With allies at City Hall, the Workers Club agitated for higher pay at Brown and rejected the company’s offer of a 5% raise. Workers threatened to strike, but plans changed when Brown threatened to declare bankruptcy.

When a bail-out plan with pay cuts was proposed, workers and their friends at City Hall said no. Instead, Mayor Bergeron led negotiations for a different bailout scheme, one with no pay cuts. They did, however, let Brown pay reduced taxes, then cut a deal with the State for a $650,000 emergency loan to cover the shortfall in their budget.

By 1936, left-wingers in southern New Hampshire were looking northward for leadership. Joined by communists, socialists, and leaders of Manchester’s textile worker unions, the Farmer-Labor Party went state-wide. “At a time when science and invention have made possible an economy of abundance beyond all past dreams, the great mass of American citizens are subjected to lives of extreme frustration and helplessness. Such a condition makes imperative a new political party dedicated to the achievement of economic justice and ever higher standards of human welfare,” wrote Paul Rudd, chair of the party’s Platform Committee.

“The Farmer-Labor Party arises to demand a new era—fighting, not against individual millionaires or particular corporations, but against those elements in the economic and legal system and in popular psychology, which encourage monopoly and parasitic control of the nation’s resources,” he declared.

The new party called for a graduated income tax, a sales tax, reduction of property taxes, and “decent minimum-wage standards.” Upham-Bornstein says they also backed “the right of workers to organize, to engage in collective bargaining without intimidation, and to strike without fear, and demanded old-age pensions and public ownership of utilities.”

The party hit a major bump when organized labor withdrew its support. Disturbed by the presence of Communists among the party’s supporters, the American Textile Workers Union pulled out. Meanwhile, at the national level, the AFL and the newly formed CIO decided to stick with FDR and the Democrats rather than heeding members’ call for a Labor Party.

Arthur Bergeron received the party’s nomination for governor, with hopes to get at least 3% of the statewide vote and secure ballot status. The party did pretty well in Berlin, but elsewhere failed to get much traction and fell well short of its goal. Although they hung onto influence in Berlin for a few more years, the Farmer-Labor Party lost relevance as New Deal policies took hold. By the mid-1940s, Arthur Bergeron had joined the Republicans.

Despite its failures and short lifespan, it’s worth noting that Berlin was the only city in the eastern United States where a leftist party achieved electoral success in the 20th century. Moreover, as Linda Upham-Bornstein writes, “the Farmer-Labor Party in Berlin and elsewhere and the other political protest movements of the 1930s were significant in that they influenced and informed Democratic Party domestic policy and thereby served as catalysts of political and economic change. Consequently, the reformers’ legacy was more extensive and durable than their brief ‘moment in the political sun’ might otherwise suggest.”

Ninety years later, Paul Rudd’s words bear repeating:

“At a time when science and invention have made possible an economy of abundance beyond all past dreams, the great mass of American citizens are subjected to lives of extreme frustration and helplessness. Such a condition makes imperative a new political party dedicated to the achievement of economic justice and ever higher standards of human welfare.”

——————————————————————————-

This article is largely based on two papers, “Citizens with a ‘Just Cause’: The This article is largely based on two papers, “Citizens with a ‘Just Cause’: The New Hampshire Farmer-Labor Party in Depression-era Berlin,” by Linda Upham-Bornstein, from the Fall 2008 issue of Historical New Hampshire; and “Picket Line & Ballot Box: The Forgotten Legacy of the Local Labor Party Movement, 1932-1936,” by Eric Leif Davin and Staughton Lynd, first published in Radical History Review (Winter, 1979-80) and republished as a booklet in 2018.