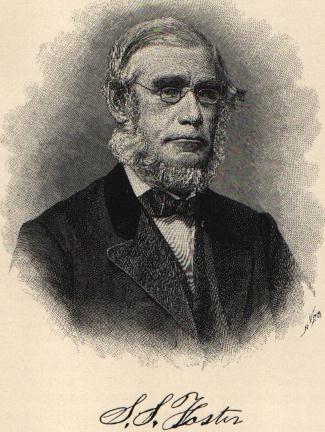

Stephen Symonds Foster was born in Canterbury, NH on November 17, 1809. The ninth child of Asa and Sarah Foster, Stephen would grow up to be a leader in the radical wing of the anti-slavery movement, for which he traveled and lectured extensively throughout the northeastern states in the decades before the Civil War. Foster would focus much of his outrage on Christian institutions, which he accused of being insufficiently committed (or not at all) to the cause of ending slavery.

Foster was a “Come Outer,” a term taken from a passage in II Corinthians 6:17 (“Wherefore come out from among them, and be ye separate, said the Lord, and touch not the unclean thing; and I will receive you,”). As a Come-Outer, Foster advocated separating from churches that would not expel parishioners who refused to endorse immediate emancipation.

On September 17, 1841, as his wife’s biographer describes, Foster entered First Congregational Church in Concord for its Sunday service. “Taking a seat with others of the congregation, he waited until the minister was about to begin his sermon. Then he rose to announce in a mild, friendly voice that as a man and a Christian he wished to speak against slavery. The astonished minister ordered him to sit down. When he continued to speak, three stalwart parishioners dragged him down the aisle and pushed him outdoors.”

Foster would repeat his distinct form of ministry at other churches, including South Congregational in Concord, from which he was ejected twice on a single Sunday (June 12, 1842). Several times he was roughed up or jailed. In a letter published in 1842 in Herald of Freedom, an anti-slavery journal published in Concord, Foster recalled, “Within the last fifteen months four times have they opened their dismal cells for my reception. Twenty-four times have my countrymen dragged me from their temples of worship, and twice have they thrown me with great violence from the second story of their buildings, careless of consequences …Twice have they punished me with fines for preaching the gospel; and once in a mob of two thousand people have they deliberately attempted to murder me, and were only foiled in their designs after inflicting some twenty blows on my head, face and neck, by the heroism of a brave and noble woman.”

“Still, I will not complain,” Foster wrote, “though death should be found close on my track. My lot is easy compared with those for whom I labor,” i.e., those who were enslaved.

His close friend, Parker Pillsbury, who accompanied Foster on lecture tours and shared his “Come Outer” ideology, would later write, “Mob violence was ever my aversion and dread, till deep in the midst of it. Brave old military heroes have often told me that they trembled at the outset, and till after the first few shots had been exchanged. Then there was no more fear. I could well understand them. But not so my friend Foster. He seemed ever cool and serene, before and through the fiercest encounters. Nor did any one ever see him exultant, in his most brilliant successes.”

Not as prolific a writer as Pillsbury, Foster contributed numerous articles to anti-slavery publications such as Herald of Freedom and published a book, The Brotherhood of Thieves; Or a True Picture of the American Church and Clergy, in which he enumerated his grievances with what he saw as Christian hypocrisy.

In 1845, Stephen Symonds Foster married Abby Kelley, another anti-slavery radical from Massachusetts, and moved with her to Worcester. For the rest of their lives, Stephen and Abby were something of a power couple among New England radicals, advocating for an immediate end to slavery, full equality for people of African descent, and full equality for women. Both of them were speakers at the founding convention of the NH Women’s Suffrage Association in Concord in 1868. He died in Worcester on September 13, 1881. She died six years later.