This was first published in the Concord Monitor on May 31, 2019, the day after New Hampshire’s state Senate overturned the governor’s veto of a death penalty repeal bill.

Oddly enough, it was a series of murders in 1997 that launched the campaign to abolish New Hampshire’s death penalty.

The killings of three police officers, the rape and murder of a 6-year-old girl, and the murder of a judge and a journalist, all within a two-month period, created political conditions that made death penalty expansion politically popular, regardless of the fact that the recent murders were largely covered already by the state’s capital murder statute.

When the 1998 legislative session opened, Republican leaders of the state House and Senate teamed up with Democratic Gov. Jeanne Shaheen to introduce a bill greatly expanding the list of crimes punishable by execution. Passage appeared likely.

But two young legislators had another idea.

Reps. Renny Cushing of Hampton and Clifton Below of Lebanon already knew each other through the anti-nuclear Clamshell Alliance when they won election to the Legislature. Instead of simply arguing against the expansion bill, they introduced a floor amendment that would abolish it altogether.

Below, then 42 years old but already a veteran legislator, was the son of a Protestant minister and brought a preacher’s touch to his speech on the House floor. “When possible,” he said, “we should choose life over death, good over evil, the possibility of redemption over destruction, of healing over revenge, love over hate.”

Speaking about the potential of every human being, even those who have committed brutal violence, to repent and gain redemption, Below lifted up the example of John Newton, a slave ship captain who was responsible for the death of scores of men, women and children. Seeking redemption from such evil, Newton became an activist in the movement to abolish the slave trade and wrote the great hymn, “Amazing Grace.”

“Who are we to deny the possibility of redemption, true change and healing?” Below asked.

“Our desire for justice, retribution, and even revenge comes to us naturally,” he continued. “But why let murderers debase our values and diminish our love for life? Why allow murderers to make us participants in perpetuating cycles of violence and revenge? Why drag all of us down by placing the blood of unnecessary killing on all of our hands?”

Renny Cushing followed, addressing the 350 House members from his perspective as the son of a homicide victim. Ten years earlier, he recalled, his father was watching the Celtics on TV when he answered a knock at the front door. “Two shotgun blasts were fired through the screen, lifting him up and hurling him backwards, the shrapnel lifting the life out of him before my mother’s eyes.”

“The most difficult thing I have ever had to ask anyone was for help in getting my father’s blood cleaned off the floor and walls,” he explained.

With his infant daughter, Grace, in her mother’s lap in the House Gallery, Cushing told a rapt audience of lawmakers: “If we let those who murder turn us to murder, it gives over more power to those who do evil. We become what we say we abhor. I do not want the state of New Hampshire to do to the man who murdered my father what that man did to my family.”

What survivors want, said Cushing, is to know the truth about what happened, to have some form of justice, and to have the opportunity to heal. Killing the killer does none of those things, he said.

When the votes were counted, the Below-Cushing amendment failed, 155-195. But the impact was powerful, and the death penalty expansion measure was voted down, too, by an even larger margin, 137-215.

The ad hoc group of death penalty opponents who worked with Reps. Cushing and Below to defeat the expansion bill soon became the N.H. Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. The coalition continued to make the case that killing those who have killed violates the moral principles of most religious traditions, that it does not deter murder or protect public safety, and that the resources spent on prosecutions in cases where execution is possible could be better spent on any number of socially useful purposes, such as giving actual aid to crime victims.

Over time, the coalition devoted additional attention to the documented cases of prosecutorial and judicial errors which placed innocent people on death row, and to the death penalty system’s demonstrated racial bias.

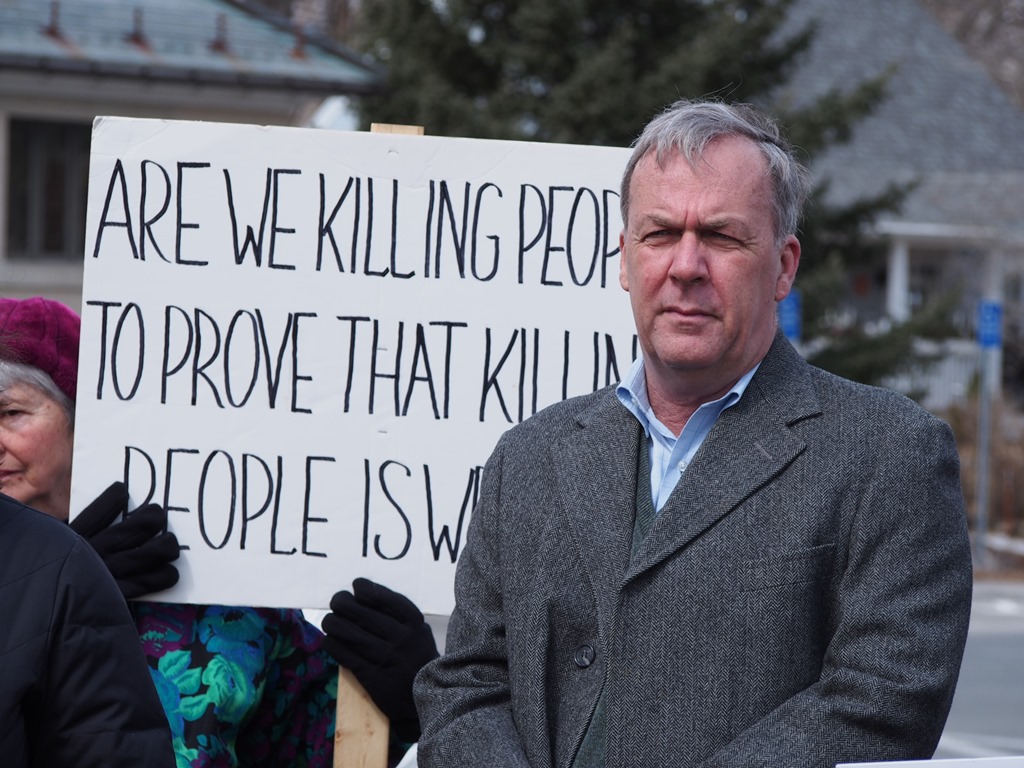

Speaking on the House floor this past March 8, Rep. Cushing, now the gray-haired chairman of the Criminal Justice and Public Safety Committee, once more told his fellow lawmakers about his father’s murder, stating, “If we let people who kill turn us into killers, then evil triumphs and we all lose.”

The 2019 repeal measure passed the House by a vote of 279 to 88, and later cleared the Senate 17 to 6. The bill was later vetoed by Gov. Chris Sununu.

Rep. Cushing took to the House floor again last week to call for members to override the governor’s veto. “The death penalty doesn’t work,” he said. “It doesn’t work for victims. It doesn’t work for society.”

Like his colleague 21 years earlier, Cushing invoked the memory of John Newton and the words of “Amazing Grace.” “I once was lost, but now am found, was blind but now I see,” a lyric that speaks to the potential we all have to atone, to change and to act in accord with deeply held values.

“New Hampshire can live without the death penalty,” he concluded. The House and Senate agreed.